His work at Open Championship venues like Turnberry and Royal Portrush have brought Martin Ebert worldwide acclaim. But, as he guides Steve Carroll through his methods, he reveals that club golf is where his heart really lies.

Your reputation has been forged on delivering spectacular changes to Open venues. How big a role do club courses play in your day-to-day work?

Your reputation has been forged on delivering spectacular changes to Open venues. How big a role do club courses play in your day-to-day work?

Turnberry and Portrush have been such big projects so the last two years have been extraordinary in that respect. We do new courses as well, although they are few and far between, but 15 per cent of our work is the Open venues, 10 to 15 per cent is on new course projects and 70 per cent is spent on wider clubs.

Word of mouth is the key. A restoration project leads to an enquiry from another nearby club and I’m hoping our name is out there enough. We don’t want clubs to say ‘they go to Open venues. They are too grand and too expensive. Their proposals will be too great for our budgets and our course.’ That’s one potential danger but that hasn’t really happened. On the whole, I think there are some other projects that do bring us some good reputations. Tom (Mackenzie) is working at Trevose and is making a huge difference to the look of the course and the bunkers. He did a good job at Delamere Forest and that led to other enquiries in that neck of the woods.

Who is Martin Ebert?

Inspired as a teenager reading through the World Atlas of Golf and designing imaginary courses, Martin Ebert graduated from Cambridge University, where he studied engineering. Having organised the university golf club’s tour of America in 1989, the experience made him determined to work in golf and he was soon offered a position to assist Donald Steel in 1990. A member of The R&A, Ebert professes to being inspired by the work of Harry Colt, Alister MacKenzie and Seth Raynor among others.

So I’m at a club that’s looking at embarking on a redesign or modernisation. Explain to me how you could go about tackling that?

It depends very much on the nature of the club. At a club that has got a great history, our first recommendation to them is that we should really try to understand how the course has evolved from the early days. Our means of doing that is to search for historical aerial photographs, look at the club website and find any history books we can look at. We look at any old photographs and ground photographs the club might have in their possession.

You can build up a little picture of how it has evolved and what features the course may have had through its history. Sometimes, it doesn’t throw up that much that will affect the proposals but, more than not, it actually does – bunker shapes or even different routing for holes. These can provide inspirations for proposals. You don’t necessarily implement the way the hole was back in 1882 or 1923 though, because the game has moved on.

“We don’t want clubs to say they go to Open venues. They are too grand and too expensive”

Turnberry is a great example. The photos, after Philip Mackenzie Ross’s redesign of the course, showed such a dramatic difference in the bunker shapes. We were doing so much new to the course, and to make use of the spectacular setting, but to find these photos and reinstate the shapes and the styles and the fairway bunkers proved to people that we had a respect and a regard for the history of the course as well as looking at how it could be improved for the modern game.

Why have some of these layouts changed so much?

So much has been lost at some of our great courses through the years.Well-meaning committees, greenkeepers and captains have produced change – sometimes for the better and sometimes not. There are so many opportunities to go in the wrong direction. This is an opportunity to rewind as well as restore and that can help shape our proposals.We can show the membership – people often object to change – and we can make the case to them – on occasions where it is not change but restoration.

So what happens when you meet a club for the first time?

So what happens when you meet a club for the first time?

We will understand the brief we have been given and the club will generally have a brief. Perhaps it is one particular hole, or the whole course. Perhaps there is a health and safety issue – it is getting to understand that. Generally, we are just looking at a few particular proposals on the course and we might say it would be best to review the whole course rather than take on the changes in isolation. They might not fit in an overall masterplan. It is making that suggestion and, if it is a course of great heritage, we should understand the history.

Then we will go out and have a good look at the course and the issues that have been discussed. I always look to do that with club officials or the course manager. It is great to have their input and we welcome input from anyone who knows the course.

Mackenzie & Ebert

Tom Mackenzie and Martin Ebert worked together for 15 years as lead designers at Donald Steel & Company before starting Mackenzie & Ebert in 2005. Between them, the duo have more than 50 years’ experience in golf course architecture and boast a stunning portfolio. They have advised six out of the 10 Open venues and around 30 of the top 100 courses in Great Britain & Ireland since their establishment. Prominent projects have included Skibo Castle, Turnberry and Killarney.

Do you like to involve club representatives throughout the process?

You can only benefit from other people’s ideas. We look to come up with our own and that’s one reason why clubs employ us but what we also need is to use our experience in judging every idea that gets through to us when we arrive at a club. Normally, they have got some good thoughts themselves. If we are appointed, we would get moving with the report or masterplan for the whole course or the specific area or feature. If we make a proposal to expand what we would do, and what the course would be, then we would do a full masterplan for the course. After an initial and very thorough look around, we are in position to produce a draft. We now go back to the club to check things out and, once we have delivered that to the club, they can take some time to think about the proposal.

The next stage is to come to the club to discuss through the proposals with them, which should end up with the start of the final masterplan. It’s something the club can follow for the next five to 10 years depending on how quickly they want to implement something. Normally that can be compressed. A project like Turnberry, for example, saw the whole golf course rebuilt in a period of one winter.

Why is the masterplan so vital to what you do?

Why is the masterplan so vital to what you do?

There is a lot in it but we think it is such an important part of a club’s planning. While it may be implemented over 5 to 10 years, hopefully that course will be set up for the next 20, 30 or 40 years. It’s a wise investment.

We now have another means of demonstrating proposals. At Hamilton Golf and Country Club, in Ontario, we took drone footage of the course and superimposed visuals over that.

They give members a chance to catch a glimpse of what’s going on as well…

Whether it is a proprietary or a members’ club, members’ approval brings them along. That’s why we have developed in the way we have in terms of procuring visuals as good as we can.

The counter point to that is if we are not con dent the visuals are going to represent what we are proposing it is then difficult to make it as good as it needs to be. Sometimes, it is difficult if you are trying to remove trees. That can be awkward. But it is far better not to have a visual than a bad one.

How involved would you be while work is going on? Do you produce the plans and then step back?

How involved would you be while work is going on? Do you produce the plans and then step back?

We want to stay very closely involved. Occasionally a proposal is implemented without our involvement with occasionally negative results. But we recommend that we are involved and the amount depends on the nature of the project. A great example is Fulford. We have implemented a masterplan over the past five years or so and the club have employed a shaper or a contractor. There has been great staff support. I would make a visit. If you are there to approve work as it is going on, you just make sure it is all going in the right direction.

Once you get an understanding with the shaper or contractor it gets easier. Even with the shapers, it is a team effort. They are providing input into the design process. I can’t live without them and they can’t live without me. Even with the most experienced people, it is essential to approve at every stage.

“You come across different attitudes. Some are a bit resistant and there are others who love the creative exercise”

What’s the key thing when working with a club?

You come across different attitudes. Some are a bit resistant and there are others who love the creative exercise and don’t feel you are making any negative comments about what they have done to the course. We are helping them make their course, and their members’ course, as good as it can be. Diplomacy is very important. It might have been a greens chairman’s pet project that doesn’t quite work and you are edging them away from that. You’ve got to get the right results for them and they are as anxious as we are to make it as good as it can be.

For more details on Martin Ebert and his course design portfolio, visit mackenzieandebert.co.uk

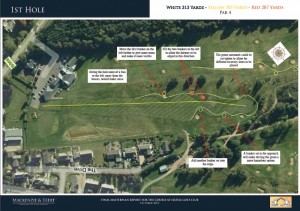

Case Study

Fulford

Fulford, regarded as one of Yorkshire’s premier clubs having hosted count- less elite tournaments, is in the midst of a Martin Ebert renovation. The course was designed by Major Charles MacKenzie and opened in 1935. It was originally a largely open heathland but, through the decades, changes from successive greens chairmen and committees altered the architect’s intentions.

“We had yover pictures from 1947, 1954 and from the 60s, 70s and 80s and you could match the pictures against each other and see how the changes had come over the years,” said Gary Pearce, the club’s general manager.

“Martin’s portfolio was fantastic, obviously. We met with him and he’d convinced us in the first half hour that he was the person to go with. We didn’t want any drastic changes to the course. We just wanted to refresh it and look at what had been put in over the past 70 years and whether they were the right ones.”

Key for Fulford was being able to carry out the work with minimum disruption to members. That meant a timescale of between six to eight years for the project.

“We recognised that we would try and do between two and three holes each year and, because we needed to keep the course open as much as possible for members to use, we’d pick a time of year to do it when business slows down at the end of September,” Pearce added. “We start the work then turf it and leave it for the whole winter to settle.”

Critically, members were involved from an early stage in the process. Pearce explained: “Right at the very start, we had a masterplan drawn up by Martin, which gave a view of the full 18 holes. We put that on the website, sent it out to members and invited them to a forum. At that meeting, about 50 to 70 pitched up, and they all had an interest in the golf course.What we wanted to achieve, and it became our joint goal, was to recreate some of the heathland aspects of the golf course, which had been lost over the years. The obvious place for that is the holes between the 6th and 13th. Over the years, a lot of silver birch had infiltrated the course. We had lost a lot of the heather and the bunker shapes had just been lost.The work he has done round there is quite special.”

Critically, members were involved from an early stage in the process. Pearce explained: “Right at the very start, we had a masterplan drawn up by Martin, which gave a view of the full 18 holes. We put that on the website, sent it out to members and invited them to a forum. At that meeting, about 50 to 70 pitched up, and they all had an interest in the golf course.What we wanted to achieve, and it became our joint goal, was to recreate some of the heathland aspects of the golf course, which had been lost over the years. The obvious place for that is the holes between the 6th and 13th. Over the years, a lot of silver birch had infiltrated the course. We had lost a lot of the heather and the bunker shapes had just been lost.The work he has done round there is quite special.”

For those clubs considering wheth- er to embark on their own redesign, or modernisation, Pearce has some clear advice.

“Do your homework. I would go and visit other courses that have had work done and ask them which architect they had used and invite them up for a chat. Get the costs right.The important thing for us was to get the members bought in to that scenario so that we could justify the cost of doing this work.When you’ve got the buy-in of the members, and of the greens staff and committee, then it is going to be a success.”

This interview was first published in The Golf Club Manager – the official journal of the GCMA. If you would like to receive the journal, either join the GCMA today, or subscribe to the magazine.

By GCMA